Ryoo Seung-wan is an accomplished director of action films inflected with comedy (Veteran) or horror (Svaha: The Sixth Finger), or telling the based-on-true-stories of Koreans stranded elsewhere in wartime. In The Battleship Island the setting was Japan in World War II; in his 2021 hit Escape from Mogadishu, the Koreans are embassy employees in Somalia. As in Steel Rain, Yang Woo-suk’s 2017 thriller, Escape from Mogadishu explores the tensions and profound mistrust of Korean-peninsula politics, and the absurdities of the artificial division imposed on those who share a language and cultural heritage.

The setting here is the Somalian capital in the final months of President Siad Barre’s dictatorship, beginning late in 1990. South Korea has a small embassy created to lobby for the African votes necessary for admission to the UN: Ambassador Han Shin-sung (Kim Yun-seok of The Fortress) and his small team are stymied in its attempts to flatter and bribe Barre’s corrupt administration by the larger, more successful North Korean mission led by distinguished old fox Heo Joon-ho (Designated Survivor).

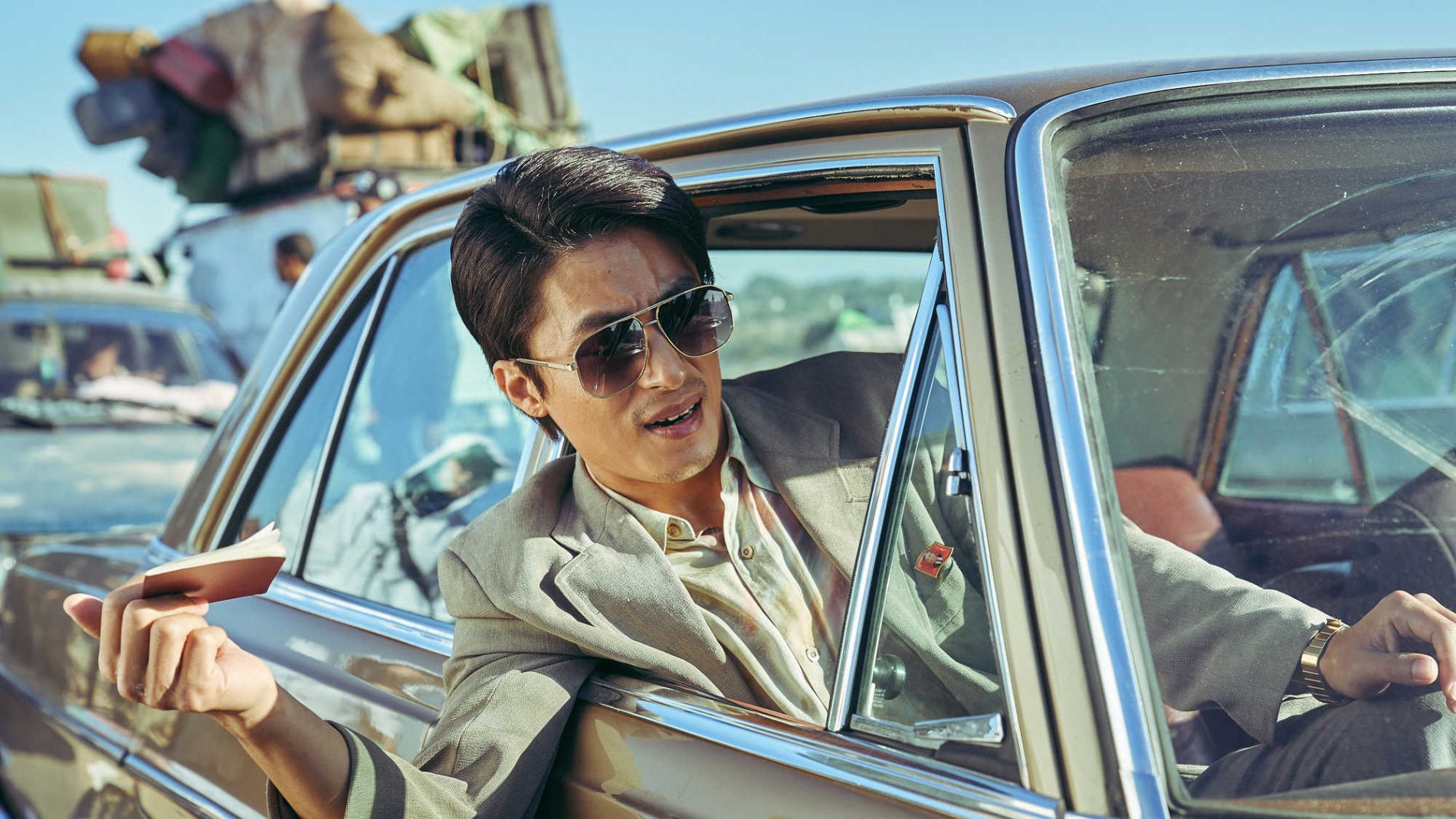

Like Veteran, the film begins with broad comedy, with a hapless embassy team barely pulling off a photo call. Then Ambassador Han’s car is hijacked by gun-toting youths who steal the suitcase of gifts from home—including a video of the Somalian team at the opening ceremony of the Seoul Olympics—and shoot up the car, making Han miss his meeting with the president. His two closest aides, functionary Gong Soo-cheol (Jeong Man-sik of Vagabond) and swaggering intelligence agent Kang Dae-jin (Zo In-sung of The King), bicker constantly: Gong, Ambassador Han says, is “more diplomat than human.” Han’s wife (Kim So-jin of The King and The Man Standing Next) insists on in-office Christian prayer meetings to the irritation of geeky translator Park Ji-eun, played by Park Kyung-hye (1987: When the Day Comes) and fellow staffer Jo Soo-jin (Kim Jae-hwa of The Royal Tailor), Gong’s wife. The South Korean mission is a doomed and chaotic failure in a country that’s about to slip into a much more serious chaos itself.

Kang Dae-jin, sent to Somalia as a demotion, is comically belligerent, shouting at everyone from his taxi driver to a policeman pointing a gun at his head. But he’s also resourceful and brave, like his North Korean counterpart Tae Joon-ki (Koo Gyo-hwan of D.P.). Both Korean missions must live by their wits to survive the escalating violence and anarchy on the streets. Neither group are strangers to authoritarian regimes. Democracy and non-military dictatorships were new in the South Korea of 1990; it was only three years since mass civil protests about the death of a student in police custody (explored in the film 1987: When the Day Comes). Swama, the South Korean embassy’s local driver, turns up badly beaten and the staff fret that he’s a rebel who should be handed over to the police. “At home they turn innocent students into Communist spies,” Gong says, arguing Swama’s case, and he’s warned not to express such heresy in front of their intelligence chief. On the North Korean side, Tae Joon-ki protests any cooperation with the South. “What’s the point in surviving here just to get purged back home?” he asks his own ambassador. Later in the film, another North Korean tells Kang Dae-jin that all diplomatic staff travelling overseas must leave one child in Pyongyang, implicitly as a hostage to ensure parents don’t defect.

When North Korea’s embassy is raided, they’re forced out in the night to find sanctuary, cornered by feral dogs and children with machine guns, trapped in firefights. The two Koreas end up in an uneasy alliance, despite deep mutual suspicion. “I heard they’re trained to kill people with their bare hands,” Jo Soo-jin warns her fellow South Koreans. The Northerners cover their children’s eyes when they pass a display case of toy mascots from the Seoul Olympics, and at first are too scared of poisoning to eat a shared meal. When they seek a flight out of Somalia, they have to approach different allies—Egypt for the North Koreans and Italy for the South Koreans—because international ideological divisions persist even in the violent anarchy of a civil war far from home.

Escape from Mogadishu was filmed in Morocco, its colourful Mogadishu stand-in a sun-bleached, dusty city of palm trees, camels and rusting cars, where boys drop their guns to play football on a beach piled high with trash. Soon it’s misted with smoke and tear gas, then comprehensively trashed by the filmmakers to reflect the brutal scorched-earth approach of both government and rebel forces. (The cinematographer here is Veteran‘s Choi Young-hwan.) Sweeping overhead shots reveal the scale of the destruction while cars try to navigate streets that are obstacle courses of burnt-out cars and corpses. Like A Taxi Driver (2017), the film becomes a heroic driving movie, with a gripping life-and-death journey through the sweltering city in cars armoured with books, home-made sandbags, duct tape and torn-off doors.

Acting is stellar in the film, especially the ambassadors and their wives—Ambassador Rim’s wife is played by Park Myung-shin of Bulgasal: Immortal Souls and Train to Busan. Forced together in the crisis, the two Koreas find a common humanity they’re not permitted to admit or express once the escape is complete. A different danger faces them outside Somalia, born of the bitter divisions of the Korean peninsula: the real fear for both groups is imprisonment (or worse) at home. The final scene of the film makes its political point, and manages both tension and poignancy.

The soundtrack by Bang Jun-seok (Veteran, The Battleship Island) is a percussive delight, supported by songs from Somalian singer Aamina Camaari, 80s funk group Dur-Dur Band, Groupe RTD from Djibouti and iconic tambour player Abu Obaida Hassan.