Bong Joon-ho’s first feature film, released in 2000, is slighter and less complex than his subsequent movies, and it failed so thoroughly at the box office that the budget for his second, Memories of Murder, was vastly reduced. At 106 minutes, it’s possibly over-long. It is both silly and macabre: before the titles we’re told that ‘No animals were harmed in the making of this film’, to reassure anyone squeamish. But the black humour of Barking Dogs is a delight, like its visual gags and exuberant moments of physical comedy. It suggests what’s to come from Bong Joon-ho over the next two decades and also stands alone as a film that explores the strange darkness of everyday life. One of the seeds of the story, the director has said, was a childhood discovery of a dog’s charred body on an apartment building’s roof, both disturbing and mystifying.

The film’s Korean title is Dog of Flanders, after a short story by the British-born writer Marie Louise de la Ramé—better known by her pen name, Ouida—from a collection published in 1872. The original story is mawkish and melodramatic, about an orphan boy who rescues an abused dog, with a tragic wintry ending straight out of ‘The Little Match Girl’. Although it was set in Belgium, the story had little impact there or elsewhere in Europe, but became—after Ouida’s death in 1908—a sensation in Japan. A much-loved children’s classic throughout east Asia, it was later adapted into versions for television and film. Few of these adaptations end with the deaths of the original story.

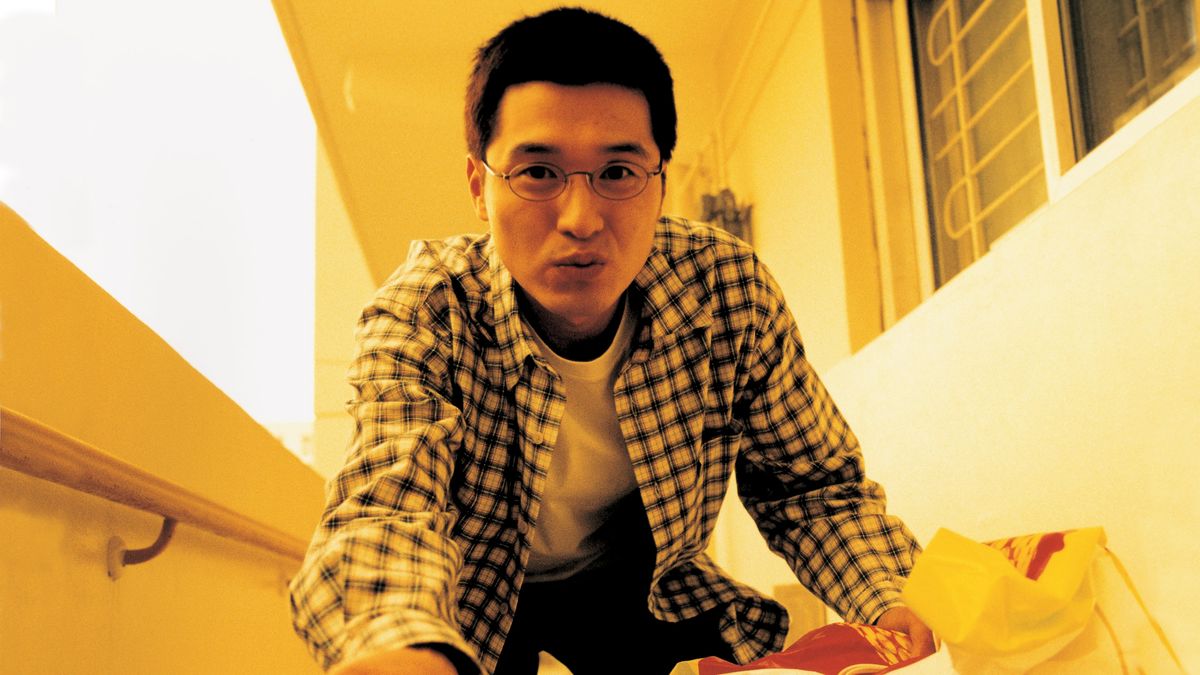

So Bong Joon-ho’s choice of movie title signals his irreverent intentions. This is not a re-make of the original story, but a subversion of it. Instead of a heart-warming (even mawkish) tale of a boy and his dog, it’s an unsettling comedy about a down-on-his-luck academic and the three dogs he dislikes. The film’s first sounds are high-pitched yaps, the noise echoing around a characterless apartment block. Dogs aren’t permitted, officially, but a number of residents have them—to the irritation of bored, frustrated Yoon-ju (Lee Sung-jae, seen more recently in the TV series Red Balloon). He spends much of his day sorting the recycling or napping, waiting for his irritable pregnant wife Eun-sil (Kim Jo-hung of Hyena) to come home from work. His ideal job, teaching at a university, seems out of reach. But all he needs, his slimy friend Joon-pyo tells him, is $10,000 to bribe the dean. (Joon-pyo is played by Im Sang-soo, director of The President’s Last Bang and the 2011 remake of The Housemaid, and like Bong Joon-ho a one-time student of sociology at Yonsei University.)

The movie begins and ends with a different sort of ideal: trees. ‘I’d like to go hiking,’ Yoon-ju tells Joon-pyo, gazing out at the woods beyond the apartment block. The camera moves back in this opening long shot to reveal his wife’s underwear pegged up to dry, evidence of another of his domestic tasks. The juxtaposition of the beauty of nature—with its promise of escape and rejuvenation—and the petty drabness of daily life is the movie’s first laugh: Yoon-ju is distracted from his beautiful view and lofty career goals because of a small dog yapping. Silencing the tiny animal is his most urgent quest, more important than taking a walk in the forest or proactively seeking work.

Obeying the comedy law of threes, Yoon-ju’s life is complicated by three small dogs: the first that he tries to dispatch off the building’s roof; the second, who is the actual offender; and a third, an impulse buy of his wife’s, who ends up lost and in mortal danger from another dog hunter. Yoon-ju’s nefarious activities draw him into the bowels of the building, with its exposed pipes and dark corners, not to mention secret activities. Bong Joon-ho, a director alert to the concrete and symbolic possibilities of spaces, would return to this in later films: in Memories of Murder (2003), the basement is the police station’s torture chamber; in The Host (2006), the creature’s lair is deep in one of the city’s sewers; in Parasite (2019), the secret space is a subterranean hideout, a sanctuary that becomes a crime scene. In Barking Dogs it’s where the seemingly benign janitor—played by veteran actor Byun Hee-bong, who appears in three other films by Bong—practices amateur butchery. It’s also where a homeless man (Kim Roi-ha, another Bong regular) sleeps in the shadows—only emerging into the light for an attempted dog barbeque on the roof.

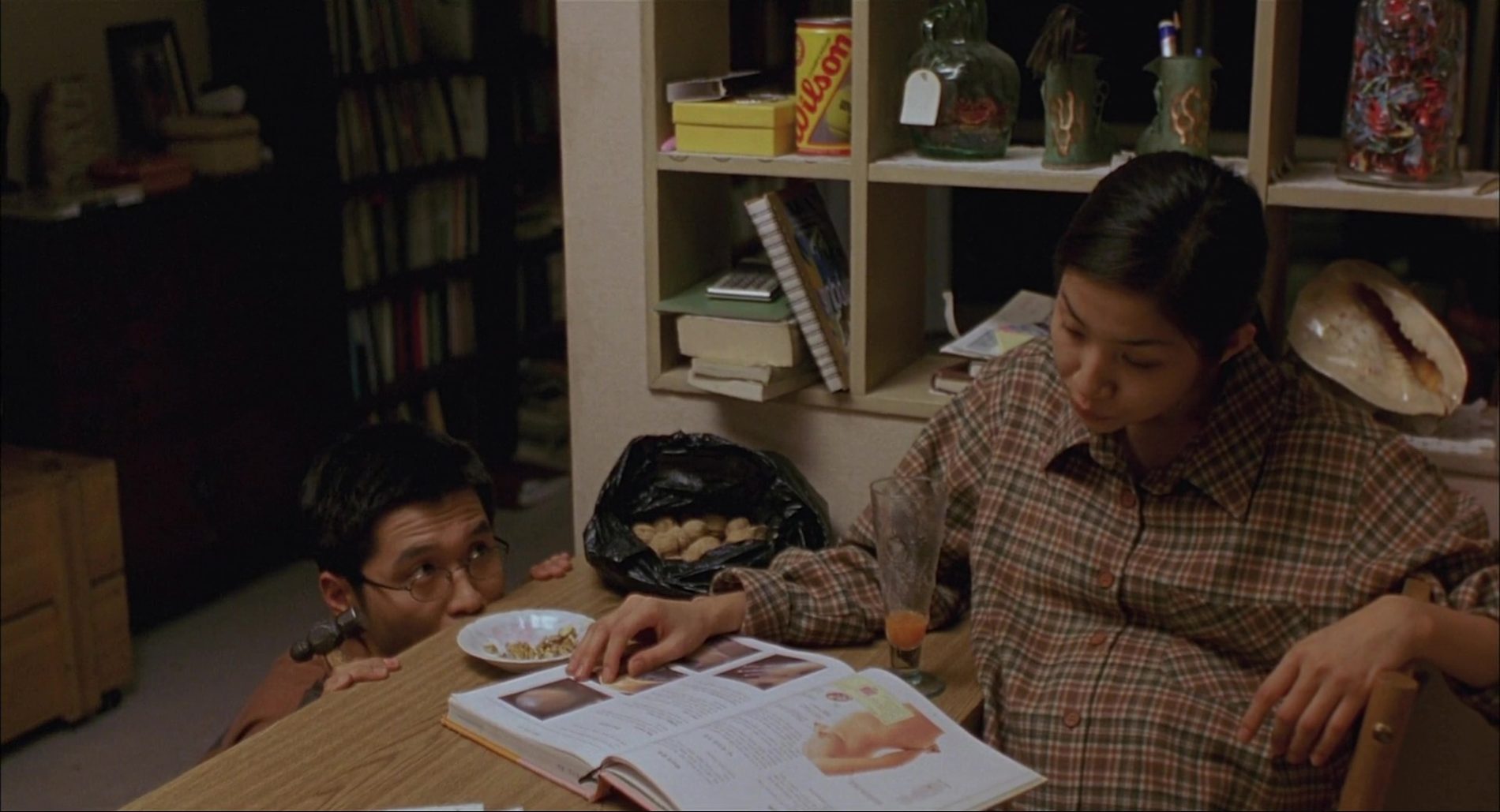

The most junior person in the building’s management office is bookkeeper Park Hyun-nam, played as a scruffy, slack-jawed ingenue by a young Bae Doona (The Host, Kingdom, The Silent Sea). Like Yoon-ju, she’s easily distracted, wandering off from her mundane job to put up posters for missing dogs or loll in her friend Jang-mi’s tiny stationery supplies shop. Our first view of both Yoon-ju and Hyun-nam is the back of their head—fitting, as the film’s two hapless main characters are always looking in the wrong places for the wrong things.

The quests in this film are anti-heroic and the protagonists’ ambitions are parodies. Yoon-ju wants to rid his building of small dogs and assemble enough money for a bribe. On the TV news, Hyun-nam sees grainy CCTV footage of a female bank clerk fighting a robber, and she dreams of similar television fame when she brings down the building’s dog kidnapper. Hyun-nam wants to come to someone’s—anyone’s—rescue, whether it’s a dog, a hospitalised old lady or the woman begging on the subway: a dozy Hyun-nam, misreading the situation, tries to offer her a seat. When she does manage to rescue a dog about to be spit-roasted, Hyun-nam imagines crowds of onlookers cheering her on. In fact, it’s such an inept rescue that the dognapper thinks she’s helping position the skewer. (‘Is that your dog?’ he asks. If not, he suggests, ‘we can eat it together.’)

Even the smaller quests of the film are farcical, like the old lady’s greedy scrambling in the road for dropped fruit, a mission so consuming she doesn’t notice when her squealing dog is stolen. Eun-sil demands not only walnuts, the only food she can bear to eat, but strawberry milk for the new pet dog, which means Yoon-ju must return to the convenience store—a task he feels is so onerous, he unrolls toilet paper in the middle of the road to demonstrate the vast distance, and make his petty point.

The voyeurism and exaggerated suspense of many scenes suggests a parodic Rear Window: dogs—and potential dog killers—are spied on neighbouring rooftops, roads and outside passageways. Yoon-ju, hiding in a wardrobe in the basement, glimpses the janitor’s grim culinary activities and overhears the gory tale of Boiler Kim, made even more sinister when the electricity fails and the janitor’s face is lit by an upturned torch. With binoculars that at first she’s not sure how to use, Hyun-nam spots the dog killer in action on the neighbouring roof.

This is a playful film, from its percussive soundtrack to its delights in repetitions and pairs. Both dog #2 and Hyun-nam’s borrowed binoculars tumble at the same time, shots intercut, off neighbouring roofs. (The editor for Barking Dogs was Lee Eun-soo, who also worked with Im Sang-soo on the movies mentioned above.) Just as the old lady loses her dog when she’s distracted by greed in the shape of fruit rolling down the road, Yoon-ju loses his wife’s dog—in that Bong Joon-ho favourite, a billowing cloud of pesticide—because he’s distracted by a scratch card he finds on the ground. We see the photocopier in Jang-mi’s shop used to make ‘Missing’ flyers: first by the young girl who owns the first dog, and later by Yoon-ju himself; to reinforce the comedic repetition, both child and man are dressed in yellow raincoats.

Yoon-ju hears two stories about men who meet accidental deaths: one is another young professor who had just bribed his way in (‘He studied abroad and all,’ Yoon-ju says, thinking of the money and time expended. ‘What a waste.’) The other is the so-called Boiler Kim, whose dead body is supposedly walled up—by callous developers—in the building’s basement. Yoon-ju is so jumpy and suggestible, he thinks a sound in the basement is the ghostly Boiler Kim; immediately after this scene, Hyun-nam falls for a crank call summoning her in the middle of the night to appear on a TV show.

At other points in the story we see more of this mirrored action, linking our central pair. Both are shown taking ill-advised control of a microphone: Yoon-ju at a karaoke bar with his desired future colleagues, singing so badly they shout at him to stop; and Hyun-nam with the building’s PA system, making a ‘missing dog’ announcement to no one in particular. In other scenes both our antiheroes have bleeding noses wadded with cotton, and both go on the run clutching small dogs; both encounter the same woman begging on the train. The movie features two tense, frantic chase scenes up and down stairs and along the external passageways of the apartment building: in the first Yoon-ju disguises himself with a pulled-down red cap, and Hyun-nam with a tugged-tight mustard hoodie. There are also paired scenes featuring a dropped shoe, one belonging to a captured perpetrator, and the other a perpetrator about to get away with murder.

Eun-sil and shop manager Jang-mi (Go Su-hee, also in The Host) are gruff, impatient foils to the protagonists, and are acutely aware of the leads’ vulnerability, too: both take action at key moments—coming up with money, tackling a suspect—to save the day. Because of them, Yoon-ju and Hyun-nam can escape the apartment block where they’ve been unhappy, bogged down by drudgery. Hyun-nam doesn’t appear on the TV news, as she dreamed, but she gets to hike in the woods with Jang-mi. Yoon-ju may end up in a university classroom, but the forested hillsides disappear behind black-out curtains. He looks wistful, as though he’s still in the wrong place, the natural world still distant and unavailable. In the movie’s final scene, the director shows Hyun-nam as we first saw her, from the back and then the side as she turns around. Her last act involves a purloined wing mirror, kicked off a car by Jang-mi earlier in the film. Hyun-nam directs it at the camera, the light bright and blinding.

Some of this will feel familiar to viewers of other Bong Joon-ho movies, not least the social commentary of an actual mirror turned on the audience: the moral compromises and misdeeds of the story, like the protagonists’ desire for increased status, is hardly unique to them. In the final scene of his next feature, Memories of Murder, the protagonist will look directly into the camera in a horrified mute appeal. That film will also begin and end with shots of the countryside, though it’s the scene of a murder rather than a location of tranquil escape and projected desires.

Bong Joon-ho’s use of the multi-level apartment block—filmed in the building in which he and his wife once lived—is a precursor of the upstairs/downstairs tensions of Parasite and its class commentary, as well as its most manic physical action. In Barking Dogs Never Bite that action is less expertly choreographed, and the social commentary is more muted. We hear of voracious 80s developers doing everything on the cheap so they could embezzle funds; in 21st-century Korea, professorial jobs are bought, and pregnant office workers get fired. Hyun-nam, a key witness in the dog barbeque arrest, is too low in social status to appear on the news, and the lowest-status person of all will be wrongly accused of all the building’s dog-related crimes. In a place of many small rules—from colour-coded recycling to authorising building stamps on missing-dog flyers—the larger transgressions are ignored.

The director is equally adept at using claustrophobic small places to suggest the entrapment or constrained lives of his characters. In Barking Dogs Yoon-ju’s worlds, like his concerns, are small. The events of his life take place in confined quarters—the wardrobe hiding place in the basement, the karaoke room, the men’s restroom—Yoon-ju’s apartment is presented as a series of small spaces, and he never roams far from it. Even when he’s out at dinner with colleagues, the shot is tight; he’s squashed into a corner. His final scene in the classroom is another image of claustrophobia. Yoon-ju looks cornered. In this first feature, Bong Joon-ho signals both his instinct for dramatic resolution and his lack of interest in traditional endings. The end of many of his films resolve the story but have the courage to leave the characters still unsettled, still unfulfilled.